For a long time I have wanted to review the book ‘Can Love last? The fate of romance over time’ by Stephen A

Mitchell, an American psychoanalytic theorist.

It is the best book on the subject I have ever read, and one that made

immediate sense to me.

The basic premise of the book is, that romance doesn’t die

of its own accord when faced with the realities of life as a couple, but rather

that it is willfully destroyed, because one or both of the lovers can’t cope

with the disturbing intensity of true romance over an extended period of time.

I think this disturbing quality of romantic passion is also the

reason why parents have always been so keen to get their children married to a

safe partner, preferably of their own choosing; as most romances depicted in literature and film show, love is

extremely disruptive and inconvenient to society.

People in love are notoriously irresponsible, selfish, and

unreliable, which is why they are bad employees, undutiful children, and irritating

parents. But people in love are also,

equally notoriously, gloriously alive and deliriously happy, which is why we all

envy people in love and like to be around them.

People commonly try to reconcile their desire for romance with

their need for a stable lifestyle by watching romantic movies and reading

sentimental novels, and then go back to their prosaic lives, not entirely

satisfied but content for the time being.

Every now and then they rebel against their passionless existence with a

fling or by finding a new partner, but as soon as the dust has settled they

will again try to choke all passion out of their new relationship, and repeat

the cycle of passion/settling down/boredom/separation.

This attitude is of course not confined to love, but

often applied to all aspects of life. We

do what we can to make life as safe as possible, and when we have achieved this

goal we rebel and do something dangerous and exciting and, usually, incredibly stupid.

I have always felt this rather unfortunate. My approach to life is, by all means make it

as safe as possible, but realise that much of the joy of life lies in the

thrill and excitement of entering new and frightening territory. I love to go out there and have adventures,

but always make sure I am well prepared, figuratively speaking, with a knapsack full of food, warm clothes, a good map, a rope just in case, and a mobile telephone for emergencies. To live life to the full, sometimes you have to throw it into the air and see where it lands - but make sure you don't throw it anywhere near a really dangerous place, like a desert or ocean!

This goes for romantic love, too. There are no certainties, no guarantees of a

happy ending. But if one is well prepared,

and judiciously plans ahead, one needn’t settle for the safe predictability of

the devoted boy next door, but can venture out and search for the true love of

one’s life.

But be warned – true love isn’t for cowards, nor for starry

eyed optimists. If you want it to last,

you need to have the sharp eyes of a sniper, the cunning of a politician, the patience

of Jacob, and the fortitude of Job – paradoxically, that is the only way you

can experience and safeguard the innocent joyous delight of true love, the joy

that was yours when you were a child, before the cruel reality of the world

intruded and crushed your happy optimism and belief in the goodness of life.

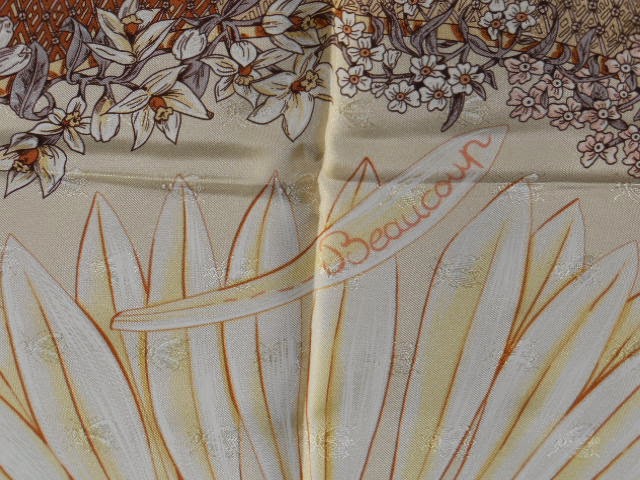

Illustrations, are, as usual, via an Hermes scarf. This one is called Amour and is by Annie

Faivre. It is a jacquard – notice the

bees that are woven into the fabric? In

case you notice the difference in colours, these are actually photos of two

scarves – same design, different colour-ways.

Happy post St Valentine’s Day! (sorry I am a bit late)

I cannot recommend the book ‘Can Love last? The fate of romance over time’ by Stephen A

Mitchell enough, and paste below, after the photos, a selection of quotes, as a

taster.

Authentic romance is hard to find and even harder to

maintain. It easily degrades into

something else, much less captivating, much less enlivening, such as sober

respect or purely sexual diversion, predictable companionship, or hatred,

guilt, and self-pity. (p 27)

We will find again and again that it is not that romance

itself has a tendency to become degraded, but that we expend considerable

effort degrading it. And we are

interested in degrading it for very good reasons. (p 28)

The need for a wholly secure attachment is powerful for both

children and adults. When patients

complain of dead and lifeless marriages, it is often possible to show them how

precious the deadness is to them, how carefully maintained and insisted upon,

how the very mechanical, predictable quality of lovemaking serves as a bulwark

against the dread of surprise and unpredictability. Love, by its very nature, is not secure; we

keep wanting to make it so. (p49)

The unconscious contract that parallels many legal marriage

contracts is the agreement to pretend to be permanently, unalterably,

impossibly bound – an agreement that creates the necessity for a carefully

guarded, perpetually measured distance.

Jacques Lacan captured vividly the mirage of degraded romance in the

service of illusory security: ‘Love is

giving something you don’t have to someone you don’t know.’ (p50)

It is common for couples with a vibrant sex life to fear

marriage. Before marriage couples often

experience themselves as free, childlike, adventurous, and spontaneous. In marriage, they seek stability and

permanence. They identify themselves as ‘adults’

now, in a static institution. And they

attribute the deadening that comes with stasis to the institution of marriage,

rather than their own conflictual longings for certainty and permanence. Total safety, predictability, and oneness,

permanently established, quickly becomes stultifying. (p50/1)

Nietzsche suggested that our lives are transitory and

illusory. We can attribute to ourselves

and out productions an illusory permanence, like a deluded builder of

sandcastles who believes his creation is eternal. Or we can be defeated by our transience,

unable to build, paralysed as we wait for the tide to come in. Nietzsche envisions the tragic man or woman, living

life to the fullest, as one who builds sandcastles passionately, all the time

aware of the coming tide. (p55)

The lover builds the castles of romance as if they would

last forever, knowing full well they are fragile, transitory structures. Those boring, sturdy stone castles over there

will last forever. (p55)

Romantic passion requires a surrender a surrender to a depth

of feeling that should come with guarantees.

Unfortunately there are no guarantees.

Life and love are inevitably difficult and risky, and to control the

risk we all struggle to locate and protect sources for both safety and

adventure. (p55)

What is alluring in the other may be the opportunity of

making contact, at a safe distance, with the parts of ourselves we have

suppressed. (p82)

The great irony of many relationships is that the quality

for which we chose a person is often just a psychic defence against its

opposite quality. Eg, the partner

selected for his seemingly impressive stability may have adopted this behaviour

trait as a defence against a terrible internal chaos. Or a woman selected for her liveliness may be

covering up an underlying depression.

(p83)

[I note, in my experience, people who genuinely possess a

certain characteristic often seem to have it to a lesser extent than others who

only pretends to have it. This is

because when you genuinely are something, you don’t need to constantly project

this, but if you are only pretending to be something you must project this permanently,

and to a high level. For example, a

transvestite who pretends to be a woman will usually exhibit more of the ‘markers

of femininity’ – make-up, skirt, large bosom (fake), long hair, etc., than a

real woman who feels no need to prove her womanhood.

Similarly, many a woman looking for a ‘strong man’ to

protect her will fall for a guy who only pretends to be strong because of an

insecurity he is secretly ashamed of, rather than for a genuinely strong man

who doesn’t feel the need to prove his masculinity all the time.]

Erotic passion destabilises one’s sense of self. When we find someone intensely arousing who

makes possible unfamiliar experiences of ourselves and an otherness we find

captivating, we are drawn into the disorientating loopiness of self/other. We tend to want to control these experiences

and the ones who inspire them. Thus

emotional connection tends to degrade into strategies for false security that

suffocate desire. And sexual excitement

tends to degrade into those elements common to all perversions – collapsed expectations

and omnipotence, which obliterate possibilities for love. Sustaining the

unstable tension of romance and regaining romantic states over time in the same

relationship require a struggle to resist those inevitable efforts to control

unsettling experiences. (p92)

Romance in relationships is not cultivated through a

resolution of tensions. Instead it

requires two people who are fascinated by the ways in which, individually and

together, they generate forms of life they hope they can count on. It entails a tolerance of the fragility of

those hopes, woven together of realities and fantasies, and an appreciation of

the ways in which, in the rich density of contemporary life, realities often

become fantasy and fantasies often become realities. (p201)